Barbara Washburn: The Accidental Adventurer Who Mapped The Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon National Park, preserving more than 1.2 million acres of the country’s most spectacularly scenic land, has attracted more than six million visitors a year, exerting an almost magnetic pull on hikers, rafters, explorers, and tourists from all over the world. Artists and writers are also drawn to the canyon, hoping to capture its legendary beauty and breadth. But have you ever wondered, who mapped the Grand Canyon for the first time?It was done by this forgotten female mountain climber, who spent years to map the entire canyon. If you are not familiar with her cartography story, you might have heard her historic Denali ascent instead.

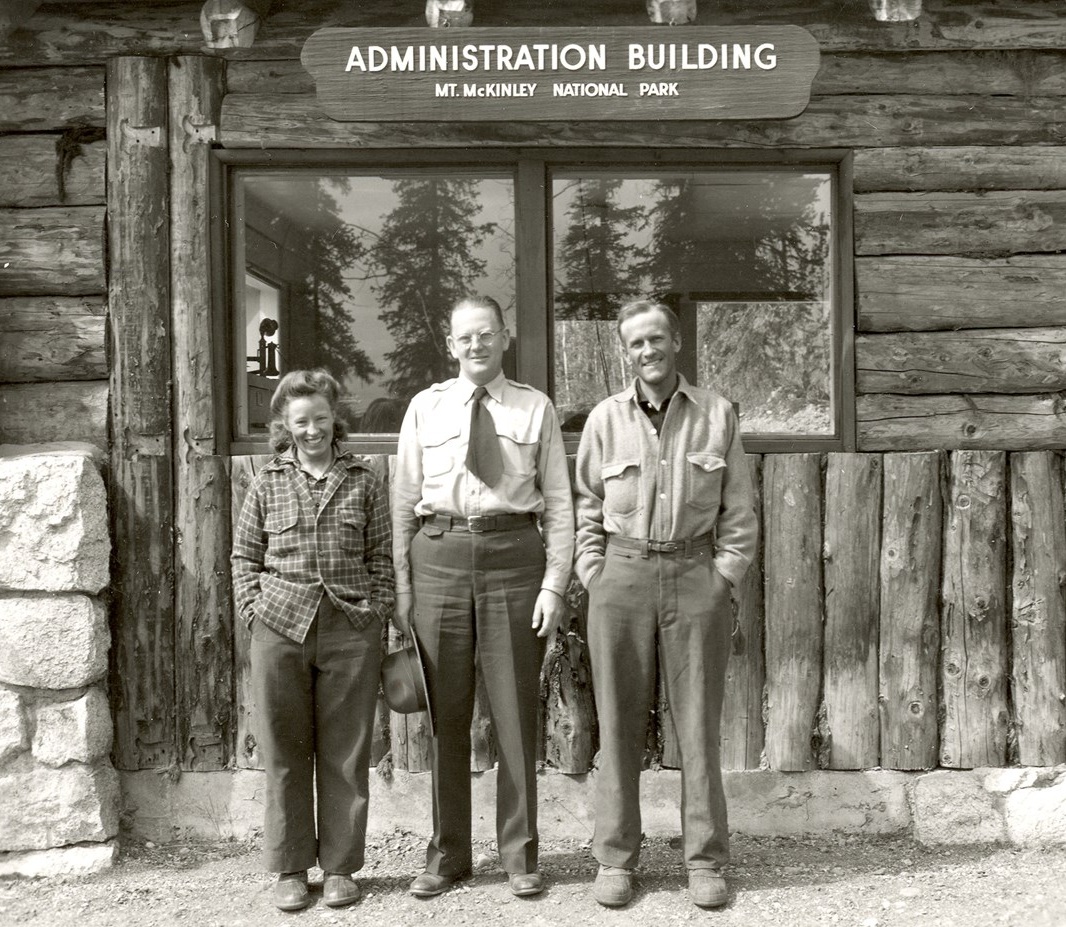

Left to right: Barbara Washburn, Mt. McKinley National Park Supt. Frank Been, and Bradford Washburn in 1947

via National Park Service

Not only did Barbara become the first woman in the world to climb Denali (Mount McKinley), the highest peak in North America, she also worked with her husband, Bradford Washburn, to map the Grand Canyon.

Barbara’s Life

via The American Alpine Club

Born in 1914, Barbara, like most women of her generation, was brought up with the idea that her place was in the home. After graduated from Smith College at the age of 24, Barbara Polk was happily employed as the secretary of the Harvard biology department. But in the spring of 1939, Clarkie, the mailman, encouraged her to apply for a job opening at the New England Museum of Natural History, whose leadership had just been taken over by an ambitious young mountaineer named Bradford Washburn.

Bradford was a mountain climber and had already established several first ascents in Alaska. After her job interview, he said he’d call her in two weeks about the job. He called her every day for two weeks, and she took the job in March 1939. Their professional relationship became more intimate, and a year after that, he proposed to her.

After their marriage in April 1940, the couple went on a trip to Alaska. Together with six other people, the couple signed up for an expedition to ascend Mt. Bertha, which stands 10,812 feet tall. One year after that, the couple, along with their team, became the first to successfully summit 13,628-foot Mount Hayes.

In 1947, Barbara and Bradford left their three children at home to climb Mount McKinley (now called Denali). The 14,600-foot climb took 70 days. She had trained for the climb by pushing a baby carriage, she later said. After nearly two months of trekking, as they neared the top, a member of the team turned around and encouraged Barbara to be the first to reach the top. “I said, ‘Who cares a rip? I don’t care—I’m perfectly happy being number two here,’” she later recalled. She eventually agreed to take the lead, and she soon stood on the summit as the first woman to look out from North America’s highest point.

No woman followed in her footsteps for another 20 years.

Barbara and Brad were married for 67 years. They were ideal companions and partners in the field, not only in Alaska but also in such monumental projects as mapping the Grand Canyon. Late in life, Barbara started writing down sketches of her adventures, in a typescript intended only to serve as a legacy for her children. But Alaska journalist Lew Freedman borrowed the only copy of the typescript, read it overnight, and persuaded her to publish it as a memoir, The Accidental Adventurer (Epicenter Press, 2001).

On September 25, 2014, Barbara Washburn died in her home in Lexington, Massachusetts, just two months shy of her 100th birthday and seven years after her husband. With her passing, America lost one of its truly great adventurers and pioneer climbers.

Mapping The Grand Canyon

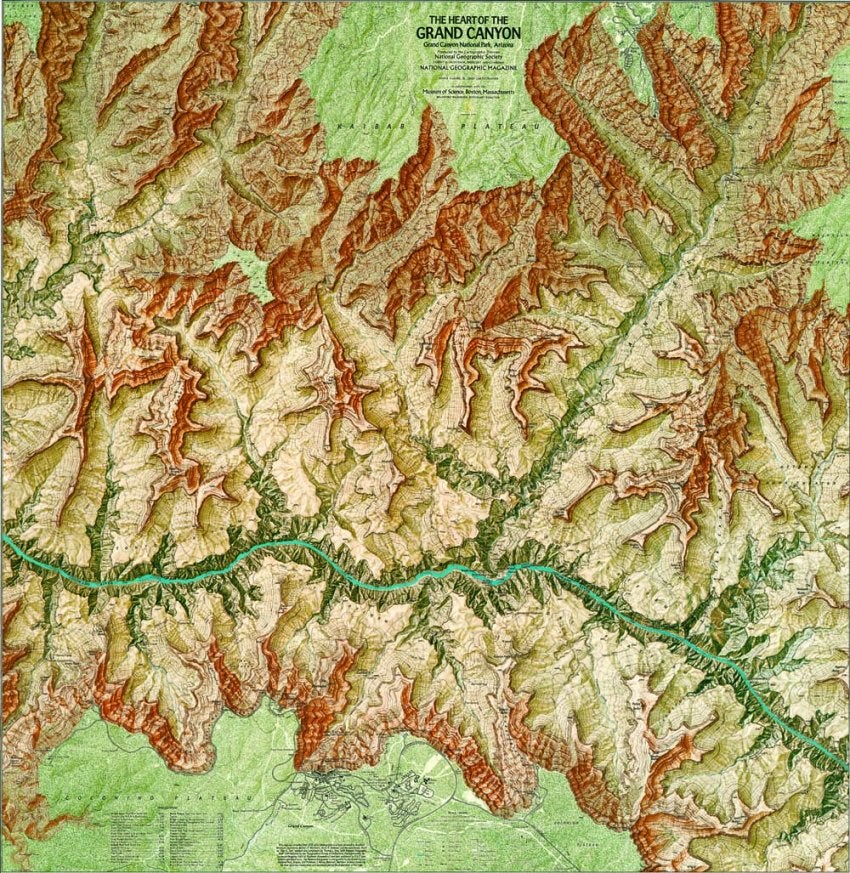

via National Geographic Maps

In the 1970s, Barbara and her husband took on an ambitious project to map the entire Grand Canyon, the results of which were published as a supplement to National Geographic magazine in 1978.

The story of Washburn’s map, as told in the 2018 National Geographic book All Over the Map: A Cartographic Odyssey, started when Washburn and his wife, Barbara, visited the Grand Canyon in 1969. They had come to acquire a boulder from the bottom of the canyon to display in front of Boston’s Museum of Science, where Washburn was the director. “We were astonished that no good large-scale map was available anywhere,” he recalled. So he decided to make one himself.

It took eight years of planning, fieldwork, analysis, drafting, painting, and negotiating to create his map of the Grand Canyon. Such an endeavor would be unheard of in today’s digital world.

Many of the points in their survey were extremely difficult or impossible to reach on foot, so Washburn hired helicopters to get them there. With 697 helicopter landings on obscure buttes and ledges in the 1970s, the Washburns and their assistants may have been the first people to ever set foot on some of the canyon’s most remote points.

Turning all of this fieldwork into a map would turn out to be just as laborious and twice as complicated as gathering the data. Bradford’s goal was to produce a masterpiece, which meant putting together an all-star team to make the map. “Nothing quite like this has ever been done before,” he wrote to the president of the National Geographic Society.

The mapping team, which included staff members of the National Geographic Society, conducted a photographic survey before employing a then-novel technique of flying helicopters to land on unscaled peaks. After cross-checking measurements of what Mr Washburn described as “this magnificent but desiccated and vertiginous wilderness,” the team produced a map of the Inner Canyon in 1974 and then a map of the center of the Grand Canyon in 1978.

In the end, all that work paid off exactly as the Washburns hoped: the map is exceptional, both technically and aesthetically. National Geographic produced two versions of “The Heart of the Grand Canyon” map, one at the full 33-by-34-inch size and another covering slightly less territory as a supplement to the July 1978 issue of National Geographic magazine, putting it in the hands of more than ten million readers around the world.

For this cartography achievement, the Washburn couple was awarded the 1980 Alexander Graham Bell Medal from the National Geographic Society. Eight years later in 1988, the couple also received the National Geographic Centennial award together with 15 other legends like Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Edmund Hillary.

For more details about Barbara’s life and climbing adventures, listen to her oral history from the University of Alaska’s Project Jukebox.

sources: nationalgeographic.com, adventure-journal.com, publications.americanalpineclub.org, nytimes.com, visiontimes.com, wcvb.com, outsideonline.com, nps.gov

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!